THE REVIVAL OF TRADITIONAL RUG MAKING AND THE ROLE IT PLAYS IN SHAPING SOCIETY

-

Popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, the traditional method of producing hand-woven rugs evolved from the ancient art of basket weaving, dating back many thousands of years B.C. Passed down through generations, this time-honoured craft became an integral part of national culture in countries such as China, India, and Turkey as well as Ukraine. The distinctive symbolism, colours, patterns, and techniques, adopted by each country, define their identity and give the rugs their unique characteristics and style.

-

-

-

Rug-making in Ukraine has been influenced by Ukrainian folk art, dating back to pan-Slavic times. It is distinguished by bright vivid colours, predominantly red and white, and symbolic patterns like those found in rushnyk (traditional ceremonial towels) depicting images of flowers, trees and animals. Closely linked to the calendar, Ukrainian folk art portrays the changing seasons, the journey of human life, and the seasonal cycle of the farming, herding and hunting communities. It captures significant communal events such as births, marriages, and deaths and proudly celebrates the long-held traditions of community, village and country.

-

Early weavers utilised natural fibres like wool, hemp and silk, employing traditional methods involving looms, combs and shuttles to interlace warp and weft threads. This labour-intensive approach not only ensures robust durability and longevity but also allows for greater design flexibility, to produce unique and exquisite designs. It’s a controllable method of production with virtually zero waste, making the process environmentally friendly.

-

-

The late 1870s saw the resurgence of weaving in the UK, led by renowned designer William Morris who founded the popular Arts and Crafts movement, a movement that revolted against cheap industrial products in favour of the value of artistic merit. His iconic designs have stood the test of time, remain much sought-after across the globe and are as popular today as ever.

-

As with many other handicrafts, the practice of weaving in Ukraine came to a standstill during the Soviet era. Conscious efforts were made to revive traditional skills by investing in the infrastructure with institutions like The School of Ukrainian Folk Masters ((now the Kyiv State School of Applied Art), established in 1920. Artisans from across Ukraine were encouraged to pass on their skills to a new generation.

-

When the nation found itself once again under siege, the desire to uphold Ukrainian traditions intensified as a means of asserting cultural identity. There is a natural inclination to go back to your roots when the future remains uncertain. Without intervention, the age-old techniques are in danger of dying out. The main reason for its demise has been one of commercial viability. A single rug takes several weeks to make and employs a least two weavers. Finding the right skills in the modern 20th-century labour force is equally problematic. But as with anything worth fighting for, where there’s a will, there’s a way. Achieving this requires a shift in mindset and a reinvestment in skills.

-

One company, Zv’yazani did just that. Identifying a gap in the market, to satisfy their own personal desire, they set about setting up premises in Kyiv and replicating the old technique. The results have been pleasantly surprising. Not only is the demand for traditional quality evident in the volume of interest attracted across the globe but the human and cultural impact has also been significant.

-

The satisfaction of learning and preserving traditional skills and working together in solidarity to create something beautiful, cannot be underestimated.

-

The same sentiment was echoed by William Morris as he vocalised the demoralising effect of mass production on the workforce and on British society, calling for ‘art which is made by the people and for the people, as a happiness to the maker and the user.’

-

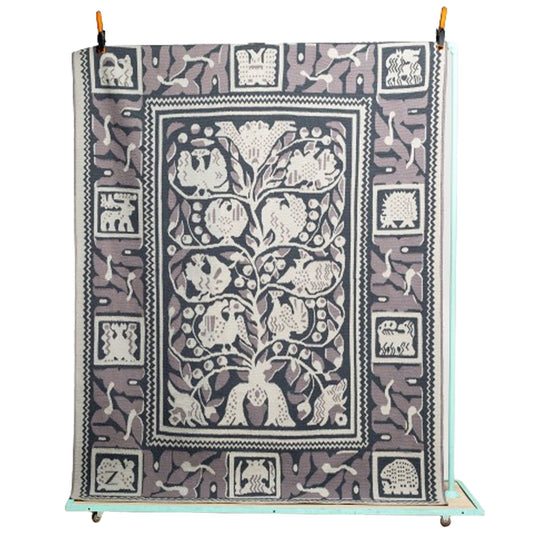

Founded by Ohla Karetnikova and Nataliia Osaulenko, the company produces intricately designed bespoke hand-woven rugs in Ukraine, employing graduates from Kyiv University. Clients can order rugs tailored to specific sizes, colours, and designs, choosing between modern styles or deeply symbolic traditional Ukrainian folk art, such as the family tree (seen here), a poignant representation of the past, present, and evolving future.

-

They not only serve to decorate our living spaces but also embody the spirit of cultural resilience and timeless appreciation of ancient, handcrafted artistry. The significance of the tree of life, a popular Ukrainian symbol, reflects this journey, with its roots firmly grounded in the past, the trunk visible in the present, and its crown arching ever onwards towards the future.

-

The tree of life symbolism is also reflected in Zv’yazani’s rug ‘June’ which celebrates the start of the summer season, the warmth of the sun and the blooming of nature, reflecting fertility at its peak.

-

-

Many of the designs take their inspiration from nature. The fish rug, made using a mirror image of carp, symbolises life cycles and constant change, taking inspiration from the familiar movement of fish, dipping, diving and darting in the sea, representing the whirlwind of life. The carp was chosen as a symbol of confidence, resilience, and courage to overcome life’s problems, a symbol that has taken on new significance in war-torn Ukraine.

-

-

‘Back to the Sea’ illustrated by Sasha Hodiaieva was inspired by the harmonious rhythm of the waves, the magnetic pull of the earth and the beauty of the sea which helps us to reflect on our lives. It is natural to be drawn to the sea for soulful contemplation.

-

The beauty and harmony of the sea and the ocean make us pause, reflect, and look around. They always bring our thoughts back, forcing us to evaluate our lives.

Sasha Hodiaieva

-

With the advance of artificial intelligence threatening to undermine our skills across the globe, perhaps it is also time for society to reflect and take action. We are already witnessing a backlash against robotic intervention in favour of the complexities and individuality of human talent. We must celebrate and appreciate a skill that has evolved over many centuries and stood the test of time. In the words of William Morris ‘The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future we are now helping to make’.

-

The importance of traditional craftsmanship and preservation of age-old techniques has never been more apparent.

The items used in the project

-

Rug Marocco

Regular price £4,414.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price per -

Rug The Fantastic Animals

Regular price £4,414.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price per -

Rug Steel Life

Regular price £4,414.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price per